Oregon can clamp down on multinational corporations shifting profits overseas, create a more level playing field for Oregon businesses, and raise millions in revenue by enacting worldwide combined reporting for multinational corporations.[1] That law would make it difficult for multinational corporations to avoid Oregon corporate income taxes by artificially shifting profits earned in Oregon to subsidiaries located abroad. Instituting worldwide combined reporting could raise an additional $232 million in each two-year budget period. Nearly all of the revenue would come from foreign, out-of-state, and rich investors.

Corporate tax avoidance by large, multinational corporations is part of the reason why Oregon’s corporate income tax rate has shrunk over time. Worldwide combined reporting is a smart, effective way Oregon can make corporations pay their fair share to support schools and essential services.

Tax avoidance by multinational corporations is costing Oregonians dearly

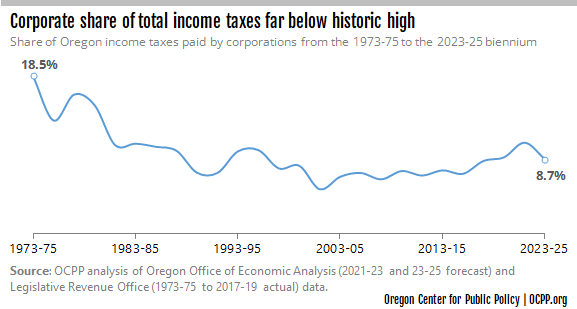

Over the past five decades, the Oregon corporate income tax has declined dramatically as a source of revenue to fund the public services that support economic opportunity and a decent quality of life for all Oregonians. The overwhelming majority of income taxes collected by the state of Oregon go to fund three things: education, public safety, and health and human services.[2] In the mid-1970s, the corporate income tax accounted for 18.5 percent of all income taxes collected in Oregon. That share is projected to be 8.7 percent in the coming budget period.[3]

One of the factors driving this decline has been multinational corporations avoiding taxation by shifting profits overseas. The particular mechanisms for avoiding taxes vary, but the basic strategy is the same: shift profits from the place they were earned to a place that levies little or no taxes on corporate income. This strategy requires having subsidiaries in different jurisdictions, which is why tax avoidance is largely the province of large, multinational corporations.

Oregon suffers when corporations hide profits abroad. Older studies have estimated that offshore tax sheltering costs Oregon about $175 million to $225 million per year.[4] A new, robust analysis puts the amount closer to $116 million per year.[5] Determining how much a corporation owes in income taxes to the state starts with the federal taxable income of the corporation. Oregon taxes the portion of that federal income based on the share of its total sales the company made to Oregon customers during the tax year. When a company’s federal taxable income shrinks by the shifting of profits abroad, so too does the amount subject to Oregon’s corporate taxes.

“Water’s edge” exposes Oregon to offshore corporate tax avoidance

When it comes to taxing corporations that have subsidiaries — a common structure of multinational corporations — states have a choice: tax the parent company and each subsidiary as separate entities or tax them together as one unit. The former approach opens the door for corporations to shift profits to subsidiaries outside the state, and thus avoid taxation. The latter approach, called “combined reporting,” adds up the income and expenses of all the related companies and treats them as one. This approach eliminates the tax advantage of shifting profits to related companies.[6]

Although Oregon generally follows the combined reporting approach, the state’s combined reporting requirement does not extend to foreign subsidiaries. Instead, Oregon connects to the federal consolidated tax returns, which only includes income reported within the nation’s borders. This “water’s edge” designation for corporations leaves the door open to shifting profits abroad as a way to avoid taxation.

Water’s edge was not always the law in Oregon. Prior to 1984, Oregon followed the worldwide combined reporting method, which required corporations to report all of the income and apportionment factors — the factors used to determine the share of income attributed to Oregon — from subsidiaries located abroad.[7] But then multinational corporations began a coordinated push to eliminate worldwide combined reporting, threatening to pull investment from states like Oregon, unless they instituted “water’s edge.”[8] This pressure campaign succeeded; Oregon dropped worldwide combined reporting.

Recent federal and state actions complicate the problem of tax avoidance

Recent changes at the federal and state level create even more uncertainty around the magnitude of multinational corporate tax avoidance, but it is clear that it’s a problem Oregon needs to address.

The massive Tax Cuts and Jobs Act passed by Congress in 2017 included significant reworking of international corporate tax policy in the U.S.[9] While the Act included a handful of provisions intended to rein in tax avoidance by multinational corporations, some experts question whether the new policies are effective and point out that the law created new incentives to shift profits outside of the U.S.[10] For example, the Foreign Derived Intangible Income (FDII) deduction could be promoting the offshoring of manufacturing facilities and other real assets.[11] The jury is still out on the net impact, because the years since its passage have included a global pandemic, record inflation partly driven by corporate profit seeking, and other complicating factors.[12] One study found the share of corporate profits held in tax havens may have declined slightly, but remains near record level.[13]

Another complicating factor is the passage of the Inflation Reduction Act in 2022. This included various corporate tax measures, including a Corporate Alternative Minimum Tax. It’s unclear how this measure will impact Oregon revenues as a result of corporate tax avoidance, since it is limited to certain corporations with more than $1 billion in profits and may not have a direct connection to Oregon income tax filings.[14]

Separate from changes at the federal level, the Oregon legislature’s repeal of the state’s tax haven law a few years back also makes it easier for corporations to engage in tax avoidance. Enacted in 2013, the Oregon tax haven law required multinational corporations to report on their corporate tax returns the income earned in more than 40 countries with a history of serving as tax havens — the British Virgin Islands, the Cayman Islands, and Cyprus, for example. The Oregon Legislative Revenue Office estimated that the law netted at least $20 million in corporate income tax collections in 2014.[15] In 2018, Oregon lawmakers mistakenly repealed the tax haven law under the impression that it was unnecessary, given the provisions in the 2017 federal tax act aimed at deterring offshore tax avoidance. However, as noted above, there is uncertainty about the effectiveness of those safeguards.

In short, at both the federal and state level, changes in multinational corporate tax law complicate the picture of corporate tax avoidance, but the need for state action remains.

Solution: Reinstate Worldwide Combined Reporting

Oregon can address offshore corporate tax avoidance by reinstating worldwide combined reporting, the standard that existed prior to 1984. Using the newest estimates from the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, Oregon could raise roughly $232 million each budget period to invest in schools, health care, and other essential services.[16]

Worldwide combined reporting means that Oregon would require corporations to include in their taxable income the income of all their affiliates, even those outside of the United States.[17] This would remove the incentive for corporations to shift profits overseas, since those profits would have to be included in their corporate tax returns. Oregon would then apply its usual apportionment formula — the method for calculating what portion of a company’s profits is taxable by Oregon.

|

An illustration of how worldwide combined reporting works Assume that Big International Corporation had global sales of $1 billion. Of those sales, $800 million were in the U.S., including $100 million in Oregon. The company reports that its total global profits were $150 million, with $50 million of those profits earned in the U.S.[18] Under water’s edge, the Oregon sales as a share of U.S. sales would be used to determine the apportionment factor (12.5 percent).[19] This factor would then be applied to the U.S. profits ($50 million) to reach the apportioned taxable income to Oregon ($6.3 million).[20] After applying Oregon’s corporate income tax rates, Big International would owe $465,000. Under worldwide combined reporting, Oregon’s share of the global sales (10 percent) is applied to the global profits ($150 million) to reach the apportioned taxable income to Oregon ($15 million). With the same tax rates applied, Big International would now owe more than $1.1 million in taxes to Oregon. |

Oregon could raise significant revenue from worldwide combined reporting

Oregon could raise an estimated $232 million in additional revenue per budget period by shifting to worldwide combined reporting. These dollars would be coming exclusively from multinational corporations that sell goods or services in Oregon — corporations that use Oregon’s infrastructure, public safety, and other shared services, but shift some of their profits overseas.

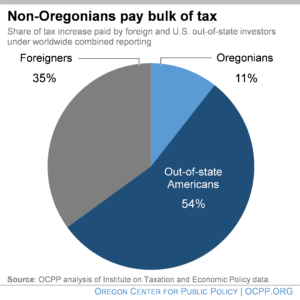

The tax would be paid by out-of-state, foreign, and rich investors

Enacting worldwide combined reporting in Oregon would raise the taxes of investors in the multinational corporations that engage in offshore tax avoidance.[21] Investors in large multinational corporations largely reside outside of Oregon, including outside of the U.S.[22] The Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP) estimates 35 percent of the revenue raised by worldwide combined reporting would be paid by foreign investors, 54 percent would be paid by American investors who live outside of Oregon, and 11 percent would be paid by Oregonians.[23]

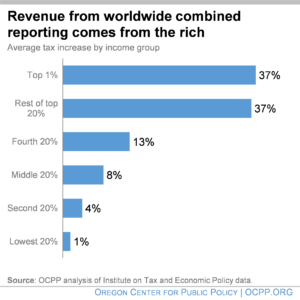

Of the Oregonians who would pay higher taxes as a result of worldwide combined reporting, research indicates the vast majority are very wealthy Oregonians who own the most corporate stocks and bonds.[24] The highest-earning 20 percent of Oregonians would capture 74 percent of the tax increase, with the top 1 percent paying one-third (37 percent). By contrast, the bottom 80 percent of Oregon taxpayers would pay close to no additional tax each year.

Worldwide combined reporting would help Oregon small businesses compete

Small businesses in Oregon would be among the largest beneficiaries of a shift to worldwide combined reporting. Offshore tax avoidance is the province of large corporations, as it requires foreign subsidiaries and a battalion of tax accountants and attorneys to exploit the loopholes. This leaves small corporations – many of them family-owned – at a competitive disadvantage against large, multinational corporations that exploit tax havens. Small corporations are also hurt by having to pay higher taxes to make up for those not being paid by the multinational corporations, or through weaker public services they rely on, such as infrastructure and workforce training. One study estimated each Oregon small business paid nearly $700 more in taxes in 2015 because of corporate tax avoidance.[25]

Objections to worldwide combined reporting are outdated and inaccurate

When Oregon abandoned worldwide combined reporting in 1984, one of the reasons was a concern that the state’s apportionment formula would deter investment in Oregon. The basis of that concern no longer exists. The corporate income tax apportionment formula determines what share of a corporation’s income a state gets to tax. In the early 1980s, Oregon employed a formula that equally weighted three factors to determine the share of income taxable in Oregon: property, payroll, and sales. Multinational corporations pushed to eliminate worldwide combined reporting, arguing that it encouraged businesses to reduce their property (factories or other facilities), and payroll (employees) in Oregon. Since then, Oregon has dropped the three-factor apportionment formula and shifted to so-called “single sales factor,” where only a corporation’s sales in Oregon count when it comes to apportioning corporate income

Multinational corporations would have no incentive to reduce investment or employment in Oregon as a result of worldwide combined reporting, now that Oregon has adopted single sales factor apportionment. With worldwide combined reporting, a multinational corporation with a large factory and many employees in Oregon would pay the same amount in taxes if they fired half of their employees as they would if they doubled their employees in Oregon. Worldwide combined reporting would increase the taxes paid by multinational corporations. Their taxes would not vary based on property investment or employment in Oregon, only their sales. Therefore, multinational corporations have no incentive to cut investment or employment as a result of Oregon shifting back to complete business activity in determining corporate taxes.

Conclusion

Returning to worldwide combined reporting is a smart, effective way for Oregon to push back against offshore corporate tax avoidance. The purported justification for eliminating worldwide combined reporting more than three decades ago no longer exists today. Meanwhile, multinational corporations have found ways to shrink their Oregon tax obligations by shifting their profits overseas. The ultimate winners in these corporate tax avoidance schemes are mainly out-of-state, foreign, and high-income investors. The losers are Oregon families and small businesses forced to endure underfunded schools and essential services.

Worldwide combined reporting could raise $232 million per budget period — funds that would go a long way in improving the quality of life and economic opportunity for all Oregonians.

—

Endnotes

[1] The policy called worldwide combined reporting sometimes goes by the name of “complete reporting” or “ending the water’s edge election.” They refer to the same policy.

[2] Legislative Fiscal Office, 2021-23 Budget Highlights Update, May 2022.

[3] Legislative Revenue Office, Basic Facts 2022; Oregon Office of Economic Analysis, March 2023 Economic Forecast.

[4] Phineas Baxandall et al., Closing the Billion Dollar Loophole: How States Are Reclaiming Revenue Lost to Offshore Tax Havens, U.S. PIRG, 2014; and Richard Phillips and Nathan Proctor, A Simple Fix for a $17 Billion Loophole: How States Can Reclaim Revenue Lost to Tax Havens, Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy and U.S. PIRG, January 2019.

[5] Carl Davis, A Revenue Analysis of Worldwide Combined Reporting in the States, Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, 2025.

[6] While Oregon is often listed among the states that require combined reporting, that is not fully the case, leaving “Oregon more susceptible to these domestic tax shelters than states that impose . . . combined reporting,” according to the Oregon Department of Revenue. Oregon Department of Revenue, Out-of-State Tax Shelters Report, January 2014, p. 12.

[7] Nancy Foran and Dahli Gray, The Evolution of the Unitary Tax Apportionment Method, 1988.

[8] Ibid.

[9] House Resolution 1, An Act to provide for reconciliation pursuant to titles II and V of the concurrent resolution on the budget for fiscal year 2018, 115th U.S. Congress.

[10] Chuck Marr, Brendan Duke, and Chye-Ching Huang, New Tax Law Is Fundamentally Flawed and Will Require Basic Restructuring, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, April 2018; Rebecca Kysar and Kimberly A. Clausing, Will the Trump tax cuts accelerate offshoring by U.S. multinational corporations? panel at Economic Policy Institute event, May 2018.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Josh Bivens, Corporate profits have contributed disproportionately to inflation. How should policymakers respond?, Economic Policy Institute, April 2022.

[13] Javier Garcia-Bernado, Petr Jansky, and Gabriel Zucman, Did the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act Reduce Profit Shifting by US Multinational Companies? NBER Working Papers, May 2022.

[14] Ernst and Young, Tax News Update: Inflation Reduction Act has state corporate income tax implications, August 2022.

[15] Daniel Hauser, Repealing Oregon’s Tax Haven Law Is a $20 Million Gamble, Oregon Center for Public Policy, February 19, 2018.

[16] Carl Davis, A Revenue Analysis of Worldwide Combined Reporting in the States, Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, 2025.

[17] Bill Parks, Past Time for California to Retire Water’s Edge, State Tax Notes, 2018.

[18] This hypothetical assumes that all the foreign sales were manufactured abroad by a foreign subsidiary, and that all of the U.S. sales were manufactured here by the U.S. parent.

[19] This calculation is $100 million (Oregon sales) divided by $800 million (U.S. sales) to reach the sales factor of 12.5 percent.

[20] Multiplying the sales factor (12.5 percent) by the U.S. profits ($50 million) results in the apportioned taxable income of $6.3 million.

[21] Cronin et al. Distributing the Corporate Income Tax: Revised U.S. Treasury Methodology, 2013, National Tax Journal 66 (1): 239-62.

[22] Steven M. Rosenthal, Slashing Corporate Taxes: Foreign Investors Are Surprise Winners, Tax Notes, October 2017.

[23] Estimates provided in February 2023 by the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. The share of taxes paid by Oregonians assumes a significant share of closely-held Oregon C-corporations engage in profit shifting, making this a conservative assumption.

[24] Tyler Mac Innis, Capital gains drive record breaking inequality, Oregon Center for Public Policy, January 2023.

[25] Alexandria Robins and Michelle Surka, Picking Up the Tab 2016: Small Businesses Bear the Burden for Offshore Tax Havens, USPIRG, November 2016.